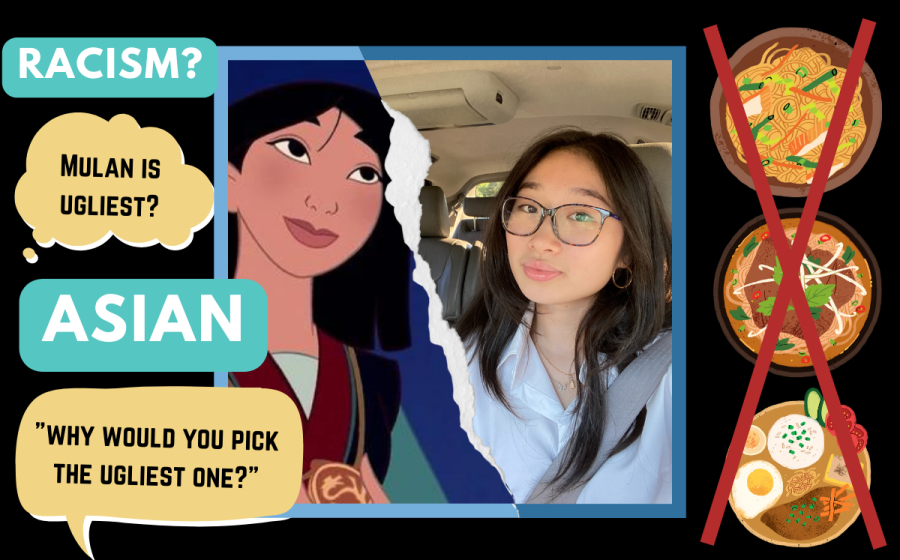

I said Mulan was my favorite princess. ‘Why would you pick the ugliest one?’

Senior Ashley Huynh shares her experience with the struggles of growing up Asian in America.

For a word to fully encapsulate a decade’s worth of humiliation, uncertainty, and self-hatred is groundbreaking. Unfortunately for me, I discovered it years too late.

I was eight years old when he asked about my favorite princess.

I teetered back onto my heels, my hands clasped behind my back as I contemplated. Ariel? No. Belle? No, I didn’t like yellow dresses. Aurora, Cinderella—

“Mulan!”

“Her?” he laughed. “Why would you pick the ugliest one?”

I awkwardly shrugged, my hands as unsure as how I felt at that moment.

He ruffled my hair and shot me a pitiful look. “Cinderella and Aurora are so much prettier, yeah?”

I nodded quickly, wanting to appease him and end this conversation, feeling lame and like I had uncool opinions.

It wasn’t lost on me that out of all the Disney princesses, Mulan looked the most like me.

Why would you pick the ugliest one?

I knew my uncle loved me.

He didn’t mean to hurt me; he replied with the intent of being honest, but in a way, this made it worse—knowing that he spoke the bleak truth. I thought about Mulan’s monolid eyes and touched my own, self-consciously. So small and slanted.

So Asian.

In the years that followed, I practiced my smile in the mirror, kept the lid on my school lunch, and Googled seemingly normal questions. But, in reality, I practiced smiling without making my eyes small, refused to eat “smelly” ethnic food near my classmates, and researched how much double eyelid surgery costs.

With every smile, lunch period, and Google search, the gap between me and my Asian ancestry widened. For the first time, my Asian heritage became a parasite I desperately and quietly wanted to surgically remove from my being. But this wasn’t evident to me at the time. Feeling ugly and embarrassed drove me to erase the indicators of my Asian background, which I believed was the root of my problems.

When peers dragged back the sides of their eyes to mimic the slanted eye shape Asians like me have, I let my heritage assume the responsibility for this. If I didn’t look like this, then none of this would be happening. When people I considered friends barked at me because it was funny and obscene that Asians ate dogs, a beloved household companion, I resented any Viets who had ever eaten a dog without understanding their financial desperation.

Essentially, I felt that so many of my problems would disappear if my Asian-ness disappeared.

The summer after my sophomore year, I served as my school’s representative in a social justice and educational equity internship with the Minority Scholars Program. During one lesson, there was an inverted pyramid figure representing the levels of racism. Words like “society” and “social institutions” were at the wide top, and at the narrow bottom of the figure rested the word “self.”

“Internalized racism,” my county sponsor said, pointing to the tip of the pyramid, “refers to the private beliefs held by an individual that foster inferiority in minorities. Marginalized groups can sometimes turn oppression on themselves, hating themselves.”

It never registered that the self-consciousness about my appearance and culture bore racially prejudiced undertones. This revelation offered unparalleled clarity. The label of internalized racism told me it wasn’t just an isolated incident.

I wasn’t crazy.

But, along with the validation came frustration and bitterness. I was angry with my uncle, who unknowingly fissured a child’s self-esteem, creating crevices for the asphalt of insecurity to fill and harden as internalized racism. Yet, as I grew older, I understood that the European colonization of Vietnam and many other countries in Asia and Africa shaped the beauty standard to be more Eurocentric.

Although I don’t excuse my uncle’s actions, I realize that his hurtful words do not accurately reflect his character but rather echo a long-standing historical issue of war, domination, and inhumanity. He, too, has endured comments and comparisons to the physically ideal (white) man from those with whom he shared and received his phenotypes. I understood that he, like me, was a victim of a vicious cycle in which we tried to eradicate the parts that made us different from the standard.

The Minority Scholars Program showed me the true parasite—the oppression marginalized groups turn on themselves, identified as “internalized racism.” In a society embedded with racism on every level, from family dynamics to institutional policies, it would be nearly impossible for a person of color to always remain impervious to it.

Learning the knowledge and language was a massive step, but one overnight procedure cannot eradicate internalized racism. Overcoming it requires long-term treatments and continuous self-work to gradually shed its impact. Regaining control over how I feel about my identity looks like eating cơm tấm at the lunch table, smiling with my eyes, and simply talking about Tết, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year that I celebrate. It means introducing myself with my ethnic last name, even if I knew teachers would struggle to pronounce it. Attending high school bedecked in my áo dài, a traditional Vietnamese garment, on International Day trumps my insistence on showing up to elementary school culture nights in regular American clothes. I embrace my bilingual background, no longer embarrassed to converse with my parents in Vietnamese or be called by my Viet name in public. Every time I’m able to do these seemingly small things, I’m filling up large holes in my identity that I tried to dig out.

Frustrated that it took 16 years to become aware of the existence and impact of internalized racism, I wondered why something so silently vicious that crept on young children wasn’t addressed in schools. I realized that openly talking about internalized racism to peers and teachers, while uncomfortable, takes power away from it. I continue to share my story to reclaim autonomy of my narrative from internalized racism and spark another’s journey of healing and empowerment.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Watkins Mill High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Ashley is an IB Diploma senior at Watkins Mill High School and Co-Editor-in-Chief for The Current, who adores books and calligraphy. She is President...

Grace Edwards • Oct 6, 2022 at 7:11 pm

I’m absolutely in love with this piece. Congratulations Ashley, you deserve and have earned this recognition. You’re representing The Current well 🙂

The AAPI community has a long way to go in order to dismantle systems of self-hatred and comparison, colonialism, and even anti-Blackness among our family members. Yet, it’s coverage like this where our stories receive the social license to be told and heard.

Excited to read more !