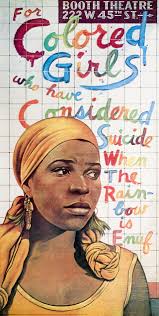

At the heart of modern contemporary Black cinema lies the undeniable presence of Tyler Perry—a true jack of all trades as a playwright, director, actor, and producer. Yet, within this notoriety lies controversy: his creative output often magnifying the complexities of Black existence, sometimes distorting them through gratuitous violence and racial stereotypes. Amid these critiques, Perry’s depiction of familial trauma in “For Colored Girls” chronicles a profound journey of pain and triumph.

The film unravels a tapestry of Black womanhood, stitched together through trauma as the movie follows seven women, each distinguished by a color signifying their burdens.

Among them is Tangie, the Lady in Orange, whose vibrant facade belies her true emotional distress. The audience bears witness to the troubling dynamic between Tangie and her mother Alice, The Lady in White. Alice berates her daughter, labeling her a “Jezebel” due to her promiscuity and further deepening the rift between them through her overt favoritism towards her other daughter, Nyla, the Lady in Purple. These tensions eventually culminate in a confrontation where Alice reveals that her father routinely called her ugly and gave her to a white man to bear “beautiful granddaughters.”

Perry skillfully examines the long-term effects of generational trauma through his multifaceted portrayal of Alice as a neglectful mother. However, as viewers, we can still sympathize with her and recognize the wounded girl she once was, helpless to a cycle beyond her scope. This exchange becomes even more sordid when Tangie tearfully reveals her own harrowing trauma, having been abused by her grandfather, while her mother Alice let it happen, even blaming her.

One standout aspect of this adaptation is its infusion of poetry from the original 1976 work, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide / When the Rainbow Is Enuf by Ntozake Shange. Tangie and Alice deliver their verses simultaneously, speaking past one another with vacancy, despite being in the same room—symbolic of the parasitic nature of their trauma bond, which continues to obstruct healing. Their overlapping verses carry a heavy message: generational trauma benefits no one, and no one is truly heard, allowing for the cycle to continue.

Tangie embodies a twisted irony. Though society elevates her due to her proximity to whiteness, she carries the brunt of the trauma, unprotected and blamed by the very mother who also faced abuse at the hands of the same man.

As I watched Tangie’s journey unfold, I couldn’t help but reflect on my own experiences as a second-generation African girl. As I prepare to leave for college, I’ve become increasingly contemplative as I reconcile with how my absence will alter the family dynamic, dysfunction aside. This particular scene has really enabled me to attempt to mend wounds with my family through uncomfortable conversations.

Tangie and Alice have one more interaction that hints at eventual coexistence. Bittersweet as the state of their fragmented relationship is, there’s also a bit of triumph in how an honest conversation led to some change, no matter how benign. Perry finds a silver lining in a volatile relationship imbued with dysfunction, remarkably without making it reductive.