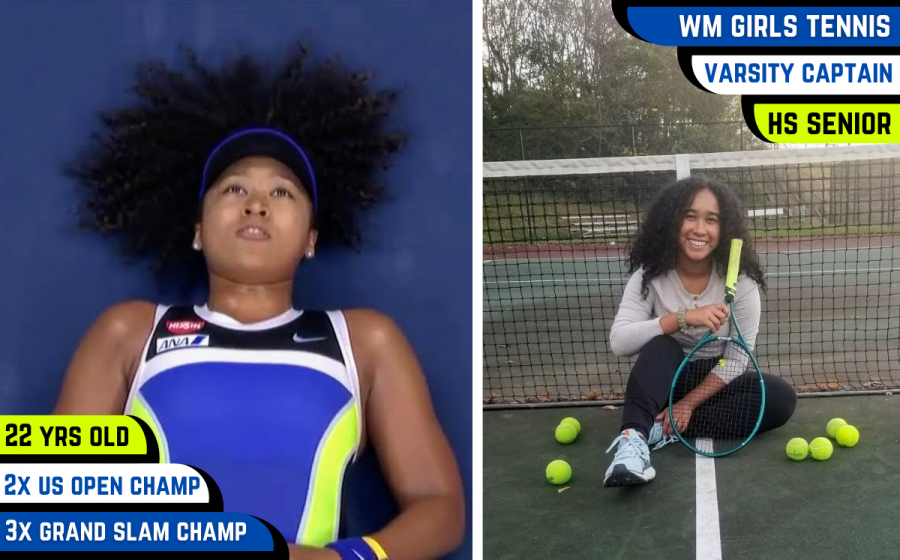

What Naomi Osaka’s 7 Masks, honoring Police Brutality victims, means to a blasian tennis player

Grace Edwards and Ashley Huynh

Editor-in-Chief Grace Edwards reflects on Naomi Osaka’s activism, bi-racial identity, and competing in the 2020 US Open.

Thank you Naomi Osaka.

As a “blasian” tennis player, I’d like to say thank you. Thank you for your stand and thank you for making a point.

On Saturday, September 12, 2020, you officially became a two-time US Open champion, while arriving to your last seven matches wearing seven black masks imprinted with the names of Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, Ahmaud Arbery, Trayvon Martin, George Floyd, Philando Castile and Tamir Rice. You won two US Opens, in addition to a third Australian Open in 2019, at just 22 years old.

Thank you for taking a stand.

“The point [was] to make people start talking [about police brutality and systemic racism]” you said. “I’ve been inside of the bubble, so I’m not really sure what’s really going on in the outside world. All I could tell is what is going on in social media.”

Yes, you live in a bubble due to your upper-middle class and celebrity status, and yet you taught us that using our occupation and our skin color as an excuse for not using our platforms to elevate lost voices, is pitiful at best. Hopefully your stance will inspire others, particularly other famous athletes, to be bold enough to “put their money where their mouths are,” and follow your example. Colin Kaepernick was one such athlete. Thank you for indirectly sending this message to those who belittle performers’ and athletes’ profession, telling you to “shut up and dribble” or “shut up and sing.”

During the rise of protests and riots, I experienced a low-grade depression. It started off as deep remorse and sorrow when I watched the full video of George Floyd’s death, but snowballed into a low-grade depression: a culmination of videos of black bodies being pulled over by the police, and frisked for mistaken identity, and the death of Civil Rights Leader John Lewis. I bled tears for Rodney King, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Trayvon Martin, and the Central Park Five, as if they were my own family members. In some moments, it is ineffable to properly express the overwhelming anguish, dejection, and hopelessness when experiencing first hand and watching the consequences of living in a black mold.

Yet, when I see men and women of all colors using their voices to uplift the under-served, I have the audacity to hope.

Thank you Naomi Osaka for making a point.

By wearing their names, you showed our generation that there are more ways to rekindle a revolution. It’s not just through protest, but with conversation. I don’t have to prove my loyalty to a cause by protesting, when the color of my skin and the spring of my curls are the symbol of the revolution. I protest with my words, my actions, educating, and by listening.

Due to the black skin coating my yellow features, I’m not seen as an Asian-American; my black body overwhelms the slightest yellow tint in my skin. As an Afro-Asian woman, I see the leverage of having a lighter skin tone. I’m exposed to family members receiving opportunities, because of the invisible leverage that gives them access to resources and connections to climb the social ladder, leaving behind those who look like me, at the bottom. These same resources and connections are not available to me, or those who look like me.

The invisible privilege is becoming more and more visible and is stealing opportunities from other minority groups, while sprouting anti-blackness stereotypical rhetoric such as “they’re lazy and stupid.” When white populations depict Asians as the “model minority,” the Asian community should use that title to uplift and support our brothers and sisters who are at the bottom of the ladder. They should not encourage the institutionalized mechanisms that depreciate and marginalize.

However, there is a relevant and appropriate concern of Racial Imposter Syndrome and credibility among young bi-racial and multi-racial activists. How can you speak up against systemic racism, if you cannot closely identify and relate to it?

It begins with story-telling. Personally, I identify as both Black and Asian, while acknowledging and experiencing first-hand the deeper cultural and intergenerational tension and prejudice that exists in Asian culture, specifically anti-blackness. It begins with conversation. We have to first confront our personal biases, those of our family and culture, before we can begin to combat systemic racism. Though I may not experience the world through Asian eyes, I can still empathize and speak up for my Asian peers in the face of discrimination, as we all should for one another.

Naomi Osaka, you illustrated the power of voice. If you are Asian, Black, Latinx, White, or purple, you have a voice, a story, and a responsibility to be involved. Yet, it is not enough to converse, we must do. We must act. It is normal to feel afraid of the inevitable scrutiny, but as the late Rep. John Lewis once said, “If you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have a moral obligation to do something about it.” This is more important.

Thank you Naomi, for wearing those seven masks, and for serving us a lesson.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Watkins Mill High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Grace Edwards is a senior at Watkins Mill High School and Co-Editor-in-Chief for The Current. She is a straight-A student who enjoys playing her violin....